Hermes sometimes stands by in his role as psychopomp. On the earlier such vases, he looks like a rough, unkempt Athenian seaman dressed in reddish-brown, holding his ferryman's pole in his right hand and using his left hand to receive the deceased. Attic funerary vases of the 5th and 4th centuries BC are often decorated with scenes of the dead boarding Charon's boat. Appearance and demeanor Charon as depicted by Michelangelo in his fresco The Last Judgment in the Sistine ChapelĬharon is depicted in the art of ancient Greece. The idea appears to have originated from the similarity between the names "Charon" and " Chronos" (a connection already made by earlier writers such as Fulgentius), the fact that both are said to be very old, and that the god of old age is said to be the child of Erebus and Night according to Cicero's De natura deorum. In Genealogia Deorum Gentilium, the Italian Renaissance writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote that Charon, who he identified as the god of time, was a son of Erebus and Night. Neither Pauly-Wissowa nor Daremberg and Saglio offer a genealogy for Charon. No ancient source provides a genealogy for Charon, except for one reference making him a son of Akmon (father of Uranus), found in the entry "Akmonides" in the lexicon of Hesychius, which is dubious and the text may be corrupt. Charon is first attested in the now fragmentary Greek epic poem Minyas, which includes a description of a descent to the underworld and possibly dates back to the 6th century BC. The ancient historian Diodorus Siculus thought that the ferryman and his name had been imported from Egypt. Flashing eyes may indicate the anger or irascibility of Charon as he is often characterized in literature, but the etymology is not certain.

The name Charon is most often explained as a proper noun from χάρων ( charon), a poetic form of χαρωπός ( charopós) 'of keen gaze', referring either to fierce, flashing, or feverish eyes, or to eyes of a bluish-gray color. Hercules and Orpheus were some known examples of beings descending to the underworld, and returning, with Charon's permission. To pay for his entry to Hades as a living mortal, Virgil's Aeneas gives Charon the Golden Bough.

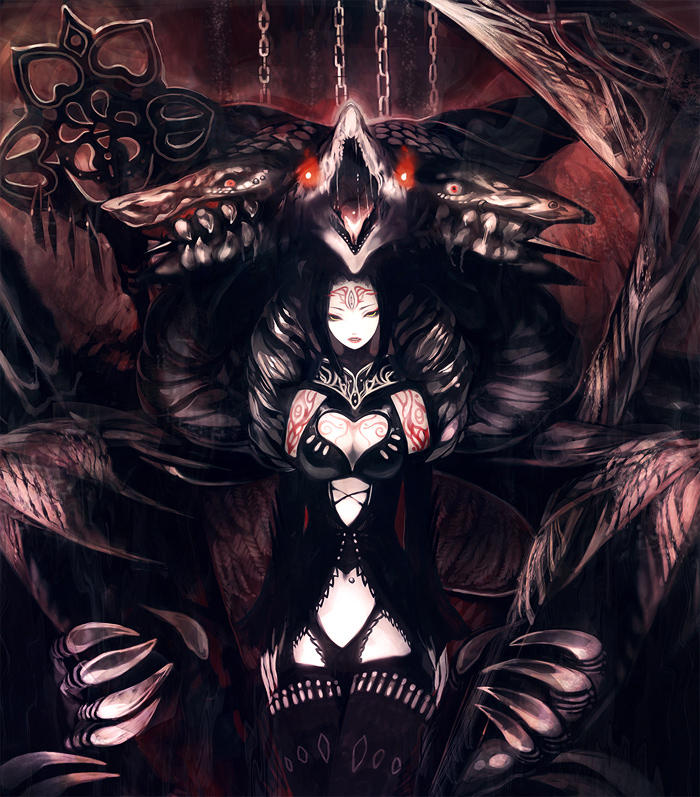

MODERN VERSION HADES ART FULL

This journey is known as catabasis, and those who undergo it may acquire partial or full immortality, either through persuasion or payment of another, more exceptional fee. Some mortals, heroes, and demigods were said to have descended to the underworld and returned from it as living beings. In Virgil's epic poem, Aeneid, the dead who could not pay the fee, and those who had received no funeral rites, had to wander the near shores of the Styx for one hundred years before they were allowed to cross the river. This has been taken to confirm that at least some aspects of Charon's mytheme are reflected in some Greek and Roman funeral practices, or else the coins function as a viaticum for the soul's journey. Archaeology confirms that, in some burials, low-value coins were placed in, on, or near the mouth of the deceased, or next to the cremation urn containing their ashes. He carries the souls of those who have been given funeral rites across the rivers Acheron and Styx, which separate the worlds of the living and the dead. In Greek mythology, Charon or Kharon ( / ˈ k ɛər ɒ n, - ən/ KAIR-on, -ən Ancient Greek: Χάρων) is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld. Get in.Not to be confused with the centaur Chiron.Īttic red-figure lekythos attributed to the Tymbos painter showing Charon welcoming a soul into his boat, c. This game comes from Hell, and it takes you back there, and it's brilliant. This is the truth of it down to the controls, which encourage you to grip the pad by the facebuttons and squeeze and squeeze and squeeze like you're one stress ball away from telling your boss to shove it. To play Hades, Roguelite aside, economy aside, loop aside, is to be furious and vengeful, to be driven by bitterness, self-hate, ennui, to be pulverisingly powerful and yet horribly efficient. There is something about polished, smartly conceived Hades, about so many of Supergiant's games which, the joyous brilliance of Pyre aside perhaps, are always too rigorous, too responsibly conceived not to know exactly what spot they're going to fit into on the shelf, which pillars they're going to present to the press - there is something about these games that are so assuredly products that reminds me that games are never ever just products. But there is something else here, something that I have always felt about games but never been able to put into words.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)